Belt, Road, and Burden

China’s Strategic Posture in an Age of Economic and Military Competition

In our previous issues, we have looked at China's military, geoeconomic, and diplomatic toolkit which are the core components of a modern state flexing for global influence. This week, we widen the lens to examine the structural forces underpinning China’s rise: its geography, natural resources, industrial and technological capacity, population dynamics, and the architecture of its governance. Together, these elements form the foundational strata of Chinese state power including some natural advantages that have helped their rise, and others which hinder it.

A quick summary of what has been covered previously:

Rapid Modernization & Restructuring: The PLA is rapidly modernizing, restructuring for "intelligentized" warfare, and strengthening Party control.

Advanced Domestic Defense: China has a sophisticated and self-sufficient defense industry, leveraging civilian tech for military use.

Increasing Regional Assertiveness: The PLA is more assertive, conducting large-scale drills (e.g., around Taiwan) and rapidly expanding its naval fleet for regional dominance.

Trade-Centric Global Influence: China's economic might stems from decades of rapid growth, now primarily through trade, surpassing major economies after its WTO entry.

Internal Economic Challenges: Beijing faces issues like trade imbalances, over-reliance on low-skill industries, and significant regional development disparities causing internal instability.

BRI as a Geopolitical Lever: The Belt and Road Initiative, a massive infrastructure project, leverages Chinese resources to create economic dependencies and expand Beijing's strategic influence globally.

Vast Diplomatic Network: China has the world's largest diplomatic presence, indicating an expansive global foreign policy.

BRI-Driven Influence: The Belt and Road Initiative leverages economic ties and infrastructure to expand China's diplomatic reach and influence.

Flexible Partnerships & Non-Interference: China favors strategic partnerships over alliances and promotes non-interference, attracting developing nations.

Active Multilateral Engagement: Beijing actively uses platforms like SCO, BRICS, and regional trade agreements to shape a multipolar world.

Countries that have joined the Belt and Road Initiative (from Council on Foreign Relations)

Geography

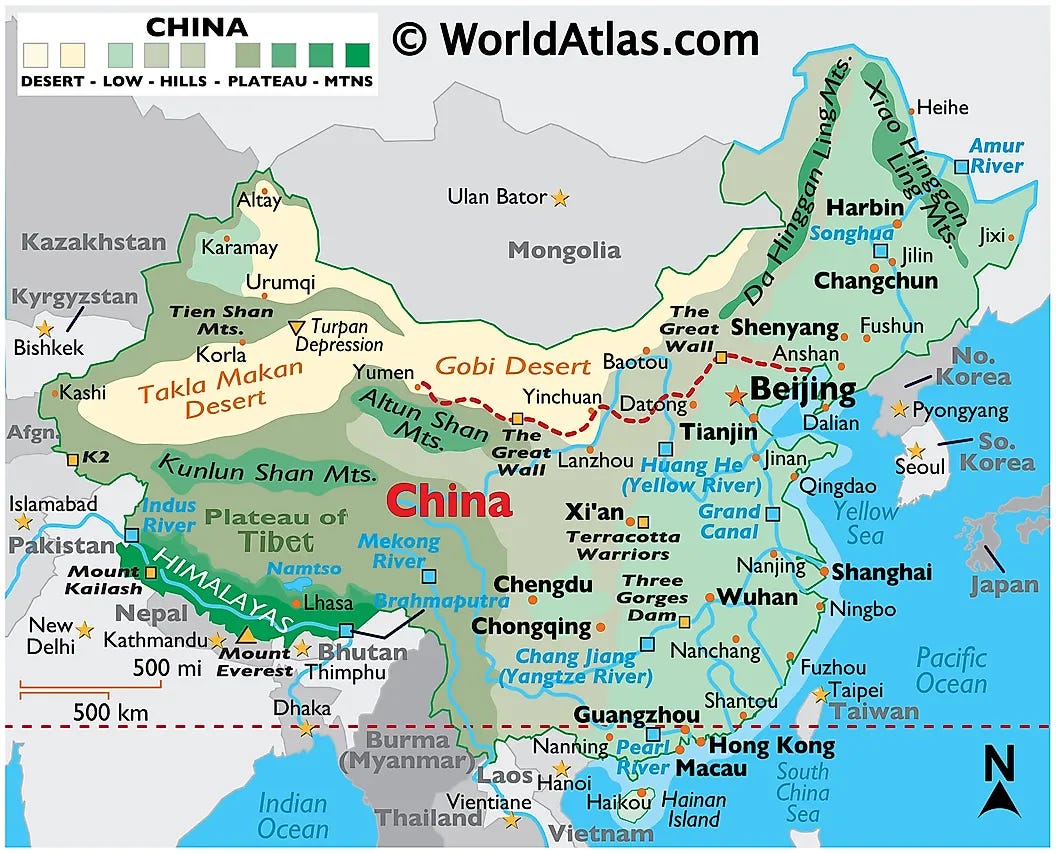

Map from World Atlas (https://www.worldatlas.com/maps/china)

China’s vast and varied geography shapes not just its internal dynamics but also its strategic posture. From the towering Himalayas and the arid expanses of the Gobi and Taklamakan deserts to the fertile, densely populated eastern plains, this terrain has historically dictated population centers, agricultural development, and infrastructure. The eastern lowlands remain the historical and economic heartland, while the mountainous and desertified west provides strategic depth in a conventional land-based defense.

Historically, Beijing viewed its extensive coastline primarily as a defensive shield. The modern geopolitical environment, however, has forced Beijing to look beyond its borders and reassess its traditionally land-focused outlook. China now finds itself tethered to the sea in ways that expose a core vulnerability - a critical dependence on secure sea lanes for the importation of vital resources, particularly energy. Roughly 62% of its oil and 30% of its natural gas are imported, much of it through narrow maritime choke points like the Strait of Malacca. This dependency turns sea lanes into strategic pressure points, prompting China’s pivot to maritime power projection and a growing naval footprint across the Indo-Pacific.

The view from China towards the open oceans with the 1st and 2nd Island Chains (from Geostrategy: https://www.geostrategy.org.uk/research/the-view-from-china/)

This maritime turn in strategic thinking also intersects with longstanding territorial disputes in the East and South China Seas. Here, sovereignty claims are less about nationalism and more about strategic depth, resource security, and regional influence. Control over disputed islands and waters means access to fisheries, potential energy reserves, and forward positions for military presence which are all central to China’s efforts to secure its maritime periphery.

Despite its substantial resource wealth, including rare-earth metals vital for high-tech industries, China’s internal geography complicates extraction and distribution. The vast distances and harsh environments that once protected the empire now pose logistical and developmental challenges, reinforcing the importance of secure external supply chains.

Natural resources

Natural resources, particularly coal, are essential inputs for China's massive industrial base, driving the phenomenal rate of economic growth seen over the last three decades. Despite growing investments in renewables, coal-fired power still accounts for roughly 62% of China’s energy consumption which is a testament to the enduring role of this resource in sustaining industrial output and economic growth.

Beyond fossil fuels, China possesses significant reserves of critical minerals, especially rare earth elements, which are essential to advanced manufacturing and national security. Among the most strategically important are:

Neodymium: Used in electric vehicles (EVs), wind turbines, consumer electronics, and missile guidance systems.

Dysprosium: Integral to EV motors, jet engines, wind turbines, and defense technologies.

Lanthanum: Key for battery production, catalytic converters, optical lenses, and petroleum refining.

These resources have underpinned China’s rapid industrialization and a state-led manufacturing surge. Core materials like iron ore (for steel), copper (for electronics and wiring), and aluminum (for a wide range of manufactured goods) have been consumed at scale to fuel economic expansion.

Find out more on Critical Minerals and China’s dominance by reading our Deep Dive available here:

In agriculture, China is the world’s largest food producer and has achieved high levels of self-sufficiency in its three staple grains: wheat, rice, and corn. In 2024, total grain output surpassed 700 million tons, thanks largely to state prioritization of food security and heavy investment in agricultural technology, improved farming practices, and modernization.

Chinese Rare Earth industrial capacity (from Statista)

Despite this success China is also the world’s largest food importer. Despite its vast territory, only a limited portion is arable and suitable for large-scale farming. This structural shortfall makes full self-sufficiency elusive, especially for key food categories like soybeans, dairy, and animal feed. The leadership in Beijing views this reliance on global food markets as a strategic vulnerability which they are actively trying to reduce through diversification of imports, overseas agricultural investments, and increased domestic production capacity.

Industrial capacity and technology

China’s industrial base remains the bedrock of its contemporary state power, but the focus has shifted from sheer volume to technological sophistication. Long the world’s manufacturing hub backed by scale, infrastructure, and state subsidies, China is now in the midst of a strategic upgrade. The goal: to lead in advanced manufacturing and high-tech sectors that define modern geopolitical clout.

At the heart of this shift is the Made in China 2025 initiative. Far more than an industrial policy, it serves as a blueprint for technological self-reliance, targeting strategic sectors such as semiconductors, aerospace, robotics, and green tech. The aims of MIC25 are clear - to break dependency on foreign technology and establish dominance in future-critical industries while fostering indigenous innovation across critical sectors.

Chinese firms are making notable strides in achieving these goals. Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC) has shown progress in mature process nodes and even demonstrated domestic capabilities in deep ultraviolet (DUV) lithography, challenging the global status quo in selected applications. In artificial intelligence, China is emerging as a formidable player. Generative AI breakthroughs are being fueled by a clear national strategy, deep public-private investment, and unique structural advantages that include language-specific data troves and a massive STEM-trained workforce.

Despite U.S. export controls targeting advanced chips, Chinese AI firms have proven adaptive. Architectural innovation, open-source ecosystems, and efficient model training which are exemplified by rising players like DeepSeek, suggest that China can achieve competitive performance with less infrastructure than its Western counterpart overcoming conventional challenges of AI development.

This technological push is not only about economic growth. It also supports military modernization, reduces exposure to external supply chain shocks, and increases diplomatic leverage. The “Dual Circulation” strategy captures this shift by promoting domestic innovation and consumption alongside selective global engagement. Together, these efforts aim to secure China’s strategic autonomy in key industries and reinforce the pillars of its state power.

Population

Alongside its industrial rise, China’s demographic trajectory has emerged as a critical and increasingly strategic challenge. For decades, the country’s massive population was viewed as a cornerstone of its economic ascent, supplying an abundant labor force that powered manufacturing-led growth. That narrative is now unraveling.

China’s population began to decline in 2022, and by 2023, India had overtaken it as the world’s most populous country. The national fertility rate, estimated between 1.0 and 1.15 children per woman, is far below replacement level. At the same time, rising life expectancy and sustained low birth rates are accelerating the aging of China’s population. This demographic shift is putting mounting pressure on social welfare systems, healthcare infrastructure, and pension funds.

The working-age population is projected to decline by more than ten percentage points by mid-century, posing a direct threat to industrial productivity and economic growth. A smaller labor pool could lead to higher labor costs, reduce economic dynamism, and shrink the talent base needed to drive innovation - especially in high-tech sectors. These trends are not just social or economic in nature. They strike at the heart of China’s long-term strategic capacity.

In response, Beijing is pushing a structural transition from labor-intensive industries to more capital- and technology-driven sectors. Policy shifts from the former one-child rule to a three-child policy, along with incentives for families and the cultivation of a so-called “silver economy” aimed at serving older citizens, signal official recognition of the stakes. Yet given the demographic momentum already in motion, these measures are unlikely to reverse the trend. Instead, China’s future state power will depend more on boosting productivity, upgrading its human capital, and drawing in global expertise, rather than relying on raw population scale as they have done in the past.

Population Density in China (from Britannica)

To that end, China has invested heavily in education. Literacy rates reached 99.83 percent in 2021, continuing an upward trend since the introduction of compulsory education in 1982. As of 2023, over 270 million Chinese citizens had attained college-level education or higher. This growing cohort of educated workers is a vital asset as the country seeks to offset its shrinking population with gains in quality and capability.

Quality of Government

Since the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) emerged victorious over the Kuomintang in 1949, it has maintained exclusive control over the Chinese state. China operates under a one-party system, in which the CCP governs without formal opposition or legal challenge. The Party not only dominates the political landscape but also integrates and oversees all major institutions of state, forming what is often described as a “party-state” structure. In this arrangement, the CCP exercises supreme authority across governance, policy, and society.

While state organs like the National People’s Congress (NPC) exist, their function is largely procedural. Real power resides within the CCP, particularly its top leadership. The general secretary of the Party (currently Xi Jinping) and the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC), the CCP’s highest decision-making body, set the strategic direction for both the state and the Party. Their decisions guide national policy across political, economic, and social domains.

Decision-making in this system follows a strictly top-down model. The PSC outlines broad priorities and directives, while lower-tier state institutions are tasked with policy implementation. These institutions, including the NPC, do not serve as checks on Party authority. Instead, they operate within the parameters set by the CCP, ensuring alignment and discipline throughout the political hierarchy.

This centralized structure allows for swift coordination and policy execution, but it also limits pluralism, suppresses dissent, and concentrates accountability at the top. As a result, the effectiveness of governance in China is closely tied to the coherence and adaptability of the CCP itself. State organs such as the NPC do not challenge party decisions.

Conclusion

As China's global ambitions intensify, its ability to sustain power projection will depend not just on military hardware or diplomatic reach but on the deeper makeup of its state structure. Their unique geography, resources, industrial capacity, demographics, and governance each offer advantages, yet come with some critical vulnerabilities. The same terrain that offers strategic depth to the west isolates vital regions and leads to separatism. The same industrial scale that led to massive market growth faces the headwinds of a shrinking, aging workforce. The same centralized governance that enables fast and unilateral action risks becoming brittle in the face of complex, modern pressures and with an aging ruling party.

In short, China’s rise is built on formidable but uneven foundations. Whether Beijing can recalibrate in time by navigating demographic decline, technological decoupling and domestication, and internal economic strains will determine the trajectory and future position either as a global power or internal tensions lead to systematic collapse.

If you like what we do here at The Pickle Gazette, please share and subscribe so that you get every new issue delivered straight to your inbox.